Price controls could mean 135 fewer new drugs in the next two decades. CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES

The reconciliation bill Democrats in Congress are about to pass will impose price controls on prescription drugs for Medicare beneficiaries (although they are couched in terms of price negotiation). Critics note that the measure would lead to fewer new drugs, fewer cures, more avoidable deaths, and higher drug prices for the private sector.

University of Chicago economist Tom Philipson estimates that because of the price controls there will be 135 fewer new drugs in the next two decades – causing a loss of 331.5 million life-years in the U.S. That is a reduction in life spans about 31 times as large as from Covid-19 to date!

Still, public opinion polls show high approval for the proposal. Why is that?

In all likelihood it’s because voters realize there are problems that need solving. Here are some better solutions.

Give Medicare enrollees access to rational insurance. In a proper insurance arrangement, people self-insure for small expenses. they can easily afford, while relying on third-party insurers for very large expenses.

Medicare drug coverage does the reverse. After a deductible (that can be as low as zero, depending on the plan), Medicare enrollees pay 25 cents of the next dollar of cost. This continues until the patient’s out-of-pocket expenses reach a “catastrophic” limit of $7,050. Above that amount the patient is responsible for 5 percent of any additional costs.

A study of 28 expensive specialty drugs found that even among Medicare enrollees covered by Part D drug insurance, the out-of-pocket spending by patients on those drugs ranged from $2,622 to $16,551. And those are annual costs! More than half (61 percent) of these drugs would require an average out-of-pocket cost of $5,444 in the catastrophic phase alone.

Congressional Democrats are also proposing to cap the annual out-of-pocket costs for all Medicare Part D enrollees at $2,000 and to impose price controls to boot.

Fortunately, there is a better way. Medicare could be redesigned to cover all catastrophic costs, leaving patients with the responsibility to pay for smaller expenses. At a minimum, seniors should be given a choice to stay in the current system or pay, say, $4 to $5 in extra monthly premium for drug insurance to limit their catastrophic exposure.

Give seniors better access to health plans that integrate pharmaceutical and medical coverage. Medicare is the only place in our health care system where plans that sell drug coverage are completely separate from plans that cover medical expenses. So, if a diabetic neglects to purchase insulin or a cancer patient neglects to pay for cancer drugs, the drug plan they are in would profit from those decisions. But the health plan that covers the patient’s medical procedures will likely incur costs that are much greater than any savings generated by failure to purchase those drugs.

That’s why the typical Medicare Advantage (MA) plan and many employer plans make insulin (and many other chronic medications) free for enrollees. Yet no Part D insurer is doing that.

The Trump administration enacted several measures that encourage more seniors to enroll in MA plans. More needs to be done.

Eliminate perverse incentives for drug plans. In any system in which health plans are forced to community rate (that is, charge the same premium, regardless of health status) the plans will have strong incentives to attract the healthy and avoid the sick. That is what is happening in the (Obamacare) exchanges where health plans discourage the sick with high deductibles and narrow provider networks and use the savings to attract the healthy with lower premiums.

Bad as things are in Obamacare, the effects are ameliorated by imperfect risk adjustment – giving extra compensation to plans with disproportionately sicker enrollment populations. In Medicare Part D, however, the risk adjustment is even less adequate, because the risk adjusters only have access to pharmaceutical information, not underlying medical information.

This gives Part D plans a perverse incentive to overcharge the users of expensive drugs and use the surplus funds to lower premiums for healthy enrollees. The entire rebate system (discussed below) is a prime example of how this works.

Give buyers access to genuine price competition. One of the most frustrating aspects of the market for Medicare-covered drugs is the practice of basing the patient’s (25%) copayment on the list price of a drug, even though the insurer pays a much lower net price, courtesy of a rebate from the drug company. In some cases, the patient’s copayment is higher than the cost of the same drug purchased from GoodRX or Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs (at 15% over the manufacturer’s cost). These discount outlets are able to offer low-priced drugs because they operate outside of the Medicare Part D system and its distorted incentives.

Why is this happening? It’s tempting to search for a scapegoat.

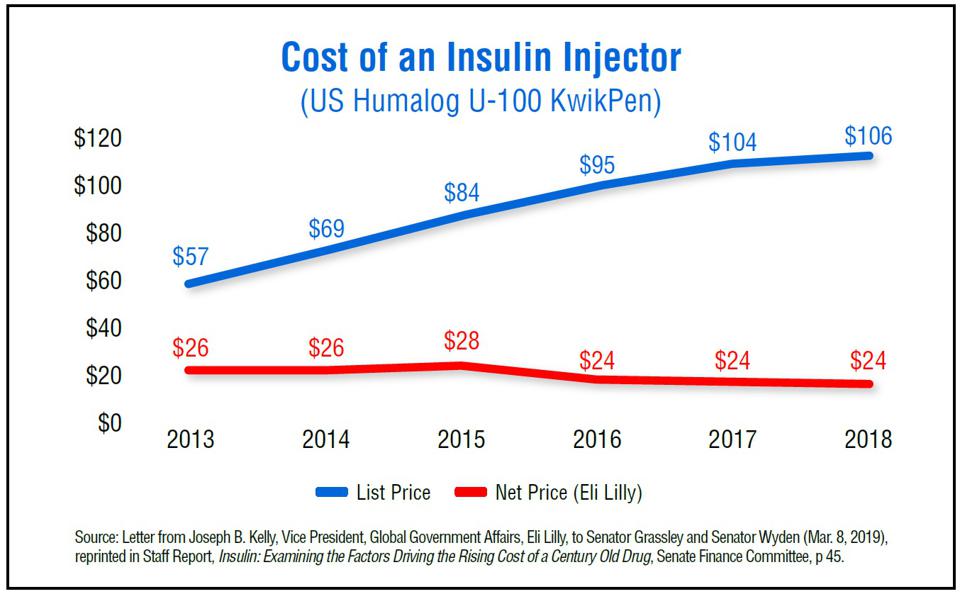

Take the market for insulin. Critics of drug manufacturers claim that the price is so high because only three companies produce insulin for the U.S. market, and that smacks of monopoly. But as the accompanying graphic shows, the manufacturer’s price in recent years hasn’t even kept up with inflation.

SOURCE: SENATE FINANCE COMMITTEE

Other critics blame pharmaceutical benefit managers (PBMs), “middlemen” who contract with insurers to lower drug costs. Are they ripping everyone off by paying rock-bottom prices to the drug companies, overcharging the patient, and pocketing the difference? To the contrary, a General Accounting Office (GAO) study finds that 99.6% of profits PBMs make from the rebate system are returned to patients in the form of lower premiums.

The perverse outcomes we observe in the market for insulin are the result of vigorous competition in the face of perverse incentives. Antitrust law makes the outcomes more perverse.

In the 1990s, drug companies could give upfront discounts to large institutional buyers, and these discounts could be passed along directly to patients. But after pharmacists brought a lawsuit under the Robinson-Patman law, upfront discounts were replaced by after-the-sale rebates instead.

One of the largest insurers in the country (Kaiser) is able to circumvent the antitrust law because it buys drugs for its own members. Kaiser negotiates upfront discounts with drug companies and passes those costs on to the patients.

Most economists think the Robinson-Patman law ought to be repealed in its entirety. Barring that, Congress should at least create a carve-out for drugs.

Virtually all of our problems in the market for prescription drugs are created by unwise public policies. The bill moving through Congress will create more harm without correcting a single one of them.

Try this one: Repeal the efficacy requirement for new pharmaceutical products required by the 1962 Food Drug and Cosmetic Act amendments That will dramatically reduce the cost of marketing new FDA approved drugs. See Mary Ruwart’s book Death by Regulation (2018)