In a recent column, I pointed out that mortgages can be major financial and tax losers. In particular, I used my company’s Maxifi personal financial planning software to answer a very simple question: If you have the cash to pay off your mortgage, how much will it raise your lifetime discretionary spending (measured in present value) if you do so?

The answer, for poor, middle class, and rich households is a ton—generally far more than a year’s after-tax earnings! Imagine having to work for an extra year simply because you failed to spend the half-hour or so required to complete this financial transaction.

My column was based on this case study posted over the summer on our company’s website. It prompted our producing and posting a second case study. The second study asks whether the financial gain from pre-paying your mortgage, whose rate is higher that what you can earn on an equal-maturity Treasury bond, combined with the tax advantages (given the new tax law) to pre-paying your mortgage are sufficiently large to outweigh the tax benefits from contributing to your 401(k). Importantly, the study assumes that reducing your own contribution wouldn’t trigger a reduced employer contribution to your 401(k) account.

Take the example of Hannah and Connor, a 30-year-old married couple making $50,000 each; i.e., $100,000 collectively. They have a $600,000 house with a $480,000 mortgage on which they’re currently paying $2,182 per month in mortgage payments. The question is whether they should stop contributing $1,500 per year, each, to their 401(k) plans and, instead, use these funds to pre-pay their mortgage. The couple realizes their 401(k) comes with lifetime tax breaks, but they also know they’re paying 3.6 percent on their 30-year mortgage (the rate prevailing when we did the analysis), whereas the corresponding return they can earn on 30-year Treasury bonds, which has the same risk, i.e., none, as their mortgage payment, is a far lower 1.944 percent (again, the prevailing rate as of the date of the analysis ).

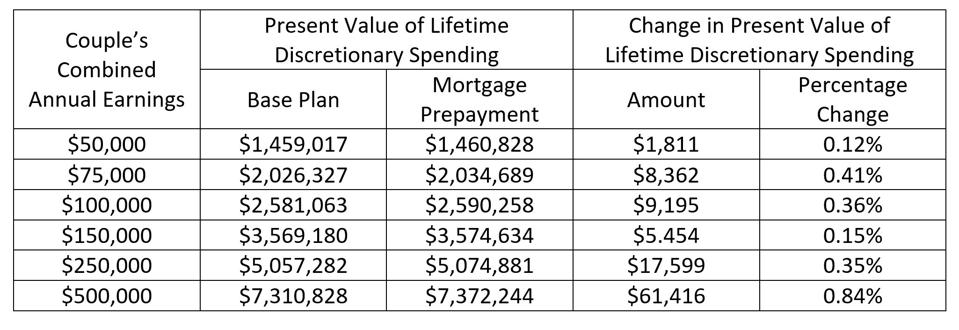

The third row in the table below shows the impact on Hannah and Connor’s lifetime discretionary spending (measured in present value) of using the money they’d otherwise contribute to their 401(k) to pre-pay their mortgage. The other rows consider financial blow downs or blow ups of Hannah and Connor. For example, row one, which posits $50,000 in combined earnings, runs the analysis with all inputs cut in half. Row six blows up all inputs by a factor of five.

The bottom line for Hannah and Connor? Pre-paying their mortgage beats making 401(k) contributions, in terms of lifetime discretionary spending, by $9,195. For the poorer and richer couples, there are also gains, either far smaller or far larger. Note that the percentage lifetime spending gain first rises than falls and then rises again as we move from the lowest- to the highest-earning households. This nonlinearity reflects the progressivity and complexities of our tax system and the relative importance of assets (and, thus, the difference in the mortgage borrowing and the Treasury lending rates) versus Social Security in funding retirement for the poor, middle class, and rich.

ECONOMIC SECURITY PLANNING, INC.

Yes, I know that most of us aren’t investing our 401(k) (or similar retirement-account assets) just in Treasury bonds that have an equal maturity to that of our mortgage. But we still need to compare pre-paying our mortgage with investing our 401(k) money in precisely such Treasury bonds. The reason is that such bonds have the same risk characteristics as our mortgages. They deliver for-sure positive income, whereas our mortgage payments represents for-sure negative income. So, we have two essentially identical securities paying different rates of return, albeit one negative and one positive. When two identical products sell for different prices, there’s an arbitrage opportunity—a way to make money with no risk by buying low and selling high. Apart from lifetime tax considerations, Connor ad Hannah face just such an arbitrage opportunity.

Yes, stocks, real estate investment trusts, corporate bonds, and other risky assets yield higher returns, on average, than do mortgage rates. But they need to do so to compensate us for the greater risk they present. Once you adjust the return on any security you might be holding in your 401(k) for risk, the appropriate comparison ends up being between pre-paying your mortgage and investing your 401(k) in the aforementioned Treasuries. Hence, even if you are holding no Treasury bonds, whatsoever, you need to assume you are investing just in such bonds to do the analysis correctly (on a risk-adjusted, apples-to-apples basis) for yourself or others.

Since the potential gains are small, would I really advise Connor and Hannah to pay down their mortgage rather than contribute to their 401(k)s? Yes, but under three conditions. First, their employers don’t cut back on their own contributions to their 401(k) accounts. Second, the couple can handle, in terms of their cash flows, the extra taxes they’ll face while doing this. And third, the couple is taking on more risk in its retirement account than, after consideration, it really wants. Re this third condition, it’s important to bear in mind that every extra dollar Connor and Hannah don’t use to pay down their mortgage but, instead, invest, at risk, in their 401(k) is, effectively, a decision to borrow to gamble in, say, stocks. Of course, investing in stocks is not like playing the slots. It’s a gamble with a positive expected return. But it is, nonetheless, a gamble. Prepaying their mortgage is not. It generates a 3.6 percent return for sure.

0 Comments