By John C. Goodman

Originally posted on Forbes, January 2016

Imagine you are running a business and selling your product for a price that is three times higher than some of your rivals. Yet despite the price difference, you continue to sell all that you produce and make a fat profit in the process. Would you voluntarily lower your price instead?

DOH. That was a rhetorical question.

Here’s a follow up: Would you feel guilty knowing that your price was so much higher than what consumers could have paid elsewhere? And if you did, would making out your deposit slips help you overcome that guilt?

Those were also rhetorical.

In any normal market this wouldn’t happen. Sellers are typically under intense competition to keep their prices down because of competition from rivals. But in the US hospital market, providers don’t compete for patients based on price. As a result, prices paid by patients and their insurers are all over the place – even for hospitals that are right next door to each other.

But, is it the hospitals fault for charging what they charge? Or is it the buyer’s fault for paying it?

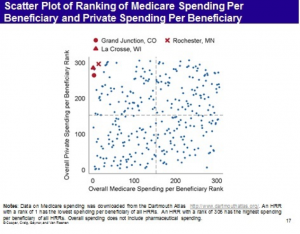

Take a look at the graph below. It is from “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured,” a December 2015 paper by Zack Cooper, Stuart Craig, Martin Gaynor, and John Van Reenen, published by a research collaboration called the Health Care Pricing Project. The authors have access to data that includes insurance claims for nearly every individual with employer-sponsored coverage from Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealth for the years 2007 to 2011. That adds up to 88 million people and it is the first time we have had a study with access to this kind of private sector data. (HT: Timothy Taylor)

There are several observations that are noteworthy.

First, among hospital referral regions (HRRs), spending per patient varies by a fact of three to one and the amounts spent are literally all over the map. This isn’t just a private sector problem. We taxpayers are paying three times as much for patients in some regions as we pay in others.

Second, the authors find that the main difference in spending is not due to a difference in the quantity of services received; it is due to a difference in the prices payers pay.

Third, within hospital regions there is even more variation. In fact, at the hospital level, the amount paid for hospital-based MRIs of lower-limb joints varies by a factor of twelve to one across the country.

Fourth, regions that were previously thought to be very low cost (e.g., Grand Junction, Colorado, La Crosse Wisconsin and Rochester Minnesota) based on Medicare data turn out to be very high cost for private patients. It appears that these regions achieve their low cost for Medicare by shifting costs to private payers. But there are also regions where that pattern is reversed. Overall, however, there appears to be no relationship between what Medicare spends and what the private sector spends.

Is there something special about medical care that makes it impossible to have the kind of competition we observe in other markets? Or does the fault lie with buyers of care – employers, insurance companies and government agencies – who seem to be willing to pay wildly different prices to hospitals in the same neighborhood? To answer that question, consider a health system in which the third-party payers weren’t there.

India is a country where there is very little private health insurance and where the role of government in providing free care is quite limited. When Indian patients enter the hospital marketplace most of the time they are spending their own money. As a result, Indian hospitals do something American hospitals do not do. Upfront package prices are the norm and hospitals compete for patients based on price and quality.

Readers are probably already aware that India is a major player in the market for international medical tourism, where their top hospitals post online such quality indicators as infection rates, readmission rates and mortality rates for different kinds of surgery and sometimes compare those statistics to those at the Mayo Clinic or the Cleveland clinic. They also manage to provide such services as heart surgery for one-tenth the price Americans typically pay. But this kind of competition is not limited to foreign patients. The entire hospital sector in India appears to be a model of efficiency.

How do they do it? By using the same continuous quality improvement techniques entrepreneurs employ in other businesses around the world:

- Keeping services patient-centered by importing routines from the hotel industry.

- Redefining job descriptions to delegate tasks to nurses and physicians’ assistants where M.D.-level skills are not required.

- Maximizing the use of capital equipment — through continuous use, say, of scanning devices and efficient operating room turnover.

- Managing the supply chain by finding the lowest-cost items (subject to quality control) in a world market.

- Vertically integrating where appropriate, including one hospital group that manufactures its own stents and diagnostic catheters.

- Investing in information technology and telemedicine.

- Using real-time monitoring of provider behavior to reduce unexplained variations in clinical practice.

Above all, these institutions have discovered that cost reduction and quality improvement often go hand in hand. Minimizing adverse events achieves both objectives. As one executive explained, “we can’t afford to have complications.” (See this 2006 Health Affairs study and an update this month.)

It appears that our crazy system of hospital prices (and the inefficiency that accompanies it) is not natural or inevitable. Instead, what we have appears to be the product of a system in which someone other than the patient pays the bill.

This article was originally posted at Forbes on January 11, 2016.

0 Comments