Standard Affirmative Cases:

The federal government should become an employer of last resort to:

- Alleviate unemployment, or

- Eliminate poverty, or

- Ensure a minimum wage, or

- Eliminate the effects of employer discrimination, or

- Produce socially desirable goods and services the for-profit sector is not producing, or

- Provide jobs that will be lost to robots.

Background theory

Historically, much of the discussion about jobs has come from non-economists who do not understand basic economic theory. So, let’s get a few basic principles out of the way.

The only socially useful purpose of work is to produce goods and services that people want to consume.

Imagine you lived in a Garden of Eden, where you could have any consumer good you wanted without work. In such a world, would it make sense to have a jobs program? Why work when you could read great books, write poetry, watch movies, play computer games, etc.?

Something that gets us close to that fantasy is expanded artificial intelligence. Suppose that AI gets so good that it could complete every conceivable task better than any human could. That means the entire GDP we have today could be produced without any human working. Would that be a bad thing? Actually, it would be a very good thing. Remember, the robots aren’t going to eat the food, drive the cars, live in the houses, etc. Robots would produce and humans would consume.

The social problem in this imaginary robot world would not be that no one has a job. The problem would be to make sure that the goods and services produced by robots were fairly distributed to the humans who consume them.

An ideal economic system is one that satisfies the most consumer wants with the limited resources we have.

That almost sounds like self-evident truth. But there is actually a lot of substance behind it. Economics says that with a competitive labor market and in a competitive capital market, maximizing consumer satisfaction requires paying each worker the amount that he or she adds to the value of the product. each input its marginal product – which is its contribution to total output. Thus a worker’s marginal product is what he or she is worth to the firm.

In the private labor market, most people are paid their marginal product.

You don’t have to study economics or read a textbook to understand the logic behind this conclusion. Suppose workers were paid less than the value of what they produce. Then a competitor could hire them away with higher wage offers and make a profit while charging the same price to consumers. Suppose they were paid more than the value of what they produce. Then their employer is likely to lose out to a competitor who pays lower wages and charges lower prices.

In order for the conclusion to be true, we only need one assumption: that employers and employees act in their own self-interest.

[Source: John C. Goodman, What Everyone Should Know About the Labor Market,”]

Interfering with a competitive labor market has unintended consequences, and they are usually all bad.

There are many arguments for supplementing the income of those at the bottom of the income ladder, say with an Earned Income Tax Credit or a Child Tax Credit. But it is hard to make an argument for interfering with people’s labor market choices and the wages they earn.

Most individuals work in order to have an income. But the social purpose of work is not to provide income. It is to make consumption possible. In the ideal world, the basket of goods that society produces should be the one that maximizes consumer satisfaction, given the resources at hand.

If wages are artificially raised—say, because of a minimum wage law or a public sector job alternative – employers will hire fewer workers and/or reduce their hours of work. This reduces the productivity of capital and makes investors less willing to invest in the businesses affected. Because labor costs are higher, the product’s prices will also be higher – causing consumers to buy less of it. At the end of the day, less is produced and less is consumed of the goods affected by the intervention.

Bottom line: consumers (including everyone who is also a worker) will end up with a basket of consumer goods that is less desirable than the one they would have preferred and could have had, but for the intervention.

[Source: John C. Goodman, What Everyone Should Know About the Labor Market,” and studies cited below.]

Negative Arguments

The American economy is already at full employment

In January 2024, the unemployment rate stood at 3.7%, a figure that economists equate with “full employment.” Why not 0%? That would mean everyone is working and no one is searching. In that case, employers with job openings would find it hard to fill those slots and employees with better earning prospects would be at work instead of interviewing for new jobs. A small amount of temporary unemployment serves an economic function similar to inventory. If retail outlets didn’t have inventory, they would frequently run out of products consumers want to buy.

[Source: CFI, “Natural Unemployment”]

Private sector employment is almost always more productive than public sector employment, other things equal.

In a full employment economy, a public sector job cannot be filled unless it pulls a worker from the private sector. Other things equal, that makes the economy less efficient and less successful in meeting consumer needs. The most important question to ask of any production system is: What incentives do people have to make good decisions rather than bad ones?

In a competitive economy people tend to get the full benefit of their good decisions and pay the full cost of their bad decisions. Workers who make good decisions tend to get promotions and raises. Those who make bad decisions tend to get laid off. If investors make good decisions, they profit. If they make bad decisions, they incur losses.

In the public sector, things are usually quite different. For example, in most cities it is very hard to fire a bad teacher or a bad police officer. Take New York:

-

It costs an average of $313,000 to fire a teacher in New York state [Thomas B. Fordham Institute, “Undue Process: Why Bad Teachers in Twenty-Five Diverse Districts Rarely Get Fired,” edexcellence.net, Dec. 8, 2016]

-

New York’s Department of Education spends an estimated $15-20 million a year paying tenured teachers accused of incompetence and wrongdoing to report to reassignment centers (sometimes called “rubber rooms”) where they are paid to sit idly. [Susan Edelman, “City Pays Exiled Teachers to Snooze as ‘Rubber Rooms’ Return,” nypost.com, Jan. 17, 2016]

-

In New York, it can also take up to six years to remove a tenured teacher. [“Undue Process: Why Bad Teachers in Twenty-Five Diverse Districts Rarely Get Fired,” edexcellence.net, Dec. 8, 2016; and Reason Magazine, “How Do I Fire an Incompetent Teacher?”]

In the last two decades of the 20th century there was an international privatization movement. In countries everywhere, governments began to sell assets – such as state-owned enterprises – to the private sector. The reason: a general recognition that the incentives in the private sector produce more efficient outcomes than those in the public sector.

In the United States, this movement saw its greatest impact in the city privatization movement in the 1990s. Prior to that time, most cities used their own employees to pick up trash, remove snow, maintain roads, trim trees, maintain water systems, etc. This meant that the typical city manager was actually running a slew of different and largely unrelated businesses. Anyone who could do that well would be a super manager – someone likely to get snapped up by a private company and paid a much higher salary. Not surprisingly, these tasks were typically not done well.

So, cities began contracting with private firms that specialized in trash collection. Private firms competed for the city contract. They then privatized other services. Contracting out to the private sector has generally meant better service at less cost for most municipalities. For it to work well city managers have to avoid the temptation of corruption and they have to be good at negotiating and managing contracts. That generally happens, but not always.

The privatization movement of the late 20th century was worldwide – at the city, state and national level. Outside of Cuba, North Korea and maybe Venezuela, it’s hard to find a country that thinks public production is superior to private production.

[Sources: Reason Foundation, Local Government Privatization 101. John B. Goodman and Gary W. Loveman, “Does Privatization Serve the Public Interest?” Harvard Law Review, December, 1991].Trying to put a floor under private sector wages with a public sector job of last resort would be an extremely inefficient way of reducing household income inequality and might even make inequality worse.

If a public sector job were available at a certain wage level, no one would have to accept a private sector job at a lower wage. In this way, public sector jobs could set a lower limit on what the private sector is paying. Here are some problems with that idea:

-

It doesn’t matter what wage entry level jobs pay.

According to McDonald’s, 1 in 8 Americans has worked at one of its restaurants. In all probability it was their first job. You don’t see many old people working at McDonald’s. (unless they are retired). If you want to do well in the labor market, you have to start somewhere.

Simple skills like showing up at work on time, following orders, being respectful to employers and customers – these are not skills most people are born with. They have to be learned. If you start out as a New York City teacher, you may never learn them.

The skills teenagers learn at their first job starts them out on the first rung of their career ladder. Basic work skills learned in an entry-level job are far more important for success in life than the entry-level wage.

-

A worker’s wage is a poor guide to household income.

In addition to wage income, people have capital income (rent, interest, capital gains, etc.), entitlement income (tax credits), etc. More importantly, workers who earn wages live in households with other people who also have incomes.

Using public sector jobs as a tool to put a floor under the wage people are paid is very much like a minimum wage.

That means that studies of the effects of minimum wage law are relevant here.

-

Many economists have pointed out that as a poverty-fighting measure the minimum wage is horribly targeted. The same principles would apply to a wage floor brought about by public sector jobs of last resort.

-

-

One study found that only 11.3 percent of workers who would benefit from raising the minimum wage come from poor households. [Joseph Sabia and Richard Burkhauser, “Minimum Wages and Poverty: Will a $9.50 Federal Minimum Wage Really Help the Working Poor?]

-

-

-

A study by Thomas MaCurdy of Stanford found that there are as many individuals in high-income families making the minimum wage (teenagers) as in low-income families. [Thomas MaCurdy, “How Effective is the Minimum Wage in Supporting the Poor?]

-

-

-

MaCurdy also found that the costs of raising the wage are passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. Minimum-wage workers often work at places whose customers have low incomes. So, raising the minimum wage is like a regressive consumption tax paid by the poor to subsidize the wages of workers who are often middle class. [How Effective is the Minimum Wage in Supporting the Poor?]

-

-

A floor on private sector wages could also hurt job opportunities for the very people it is supposed to help.

-

-

Numerous studies find that when the minimum wage is set above the market-clearing wage, fewer workers are hired by private employers and those that are hired are often forced to work fewer hours. [For a study and a review of the literature, see David Neumark, et al., “More Recent Evidence on the Effects of Minimum Wages in the United States.”]

-

-

-

Because low-wage workers get less work experience under a higher minimum-wage regime, they are less likely to transition to higher-wage jobs down the road. [Jeffrey Clemens and Michael Wither, “The Minimum Wage and The Great Recession: Evidence of the Effects on the Employment and Income Trajectories of Low-Skilled Workers.”

-

For the most part, the labor market seems to work the way textbook economics says it should work.

Economics teaches that government intervention can sometimes improve social welfare when there are “market failures.” For example, when there is monopsony (a single buyer of labor), employment will be suboptimal and the wage rate will be too low. In this case, a floor under the wage rate would increase employment and labor earnings at the same time. Yet there is very little evidence of market failure in the market for low-skilled workers.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton made the “$15 minimum wage” a plank in her presidential campaign and there was political pressure to pass “$15 dollar” state and local minimum wage laws all over that country.

Yet six years later, with hardly any new legislation anywhere, the average wage paid to fast food workers nationwide was $17.20. In some places, it was as high as $28.61. During the pandemic, we got a very clear glimpse of how well the labor market actually fits the textbook economics theory of labor market supply and demand. In a post at Forbes, John Goodman wrote:

For real eye-popping numbers, nothing quite tops the market for nurses. Before the pandemic, nurses earned an average of $73,300, or $1,400 per week. In the early stages of Covid, their pay rose by 25 percent. Then, a bidding war started as hospitals tried to fill shortages by luring prospects from other cities

The number of nurses who engage in temporary travel to take advantage of lucrative pay deals in another city rose from 5,226 in January, 2019 to 36,364 in January, 2022.

According to a Health Affairs study, traveling nurses [were] being paid between $5,000 and $10,000 a week!

A public sector jobs program would likely have no effect on wage differentials between men and women, Blacks and whites, etc.

The fact that the average wage income of women in our economy is lower than the average wage income of men is sometimes said to reflect a social problem, or perhaps even a labor market failure. But this is like comparing apples and oranges. On average, men and women don’t make the same career choices, don’t work the same number of hours, and tend to have different roles in household life. So why would anyone expect their labor market earnings to be the same?

-

Former Congressional Budget Office director June O’Neill compared the earnings of middle-aged women and men who did not have children and found that the women earn more than the men.

-

Overall, she found that career choices, lifestyle choices and work experience explain almost all the gender gap in labor market earnings.

[Source: June O’Neill, “The Disappearing Gender Wage Gap”; and Denise Venable, “The Wage Gap Myth.”]

As for racial discrimination, O’Neill and her husband Dave find that after adjusting for years of education and test scores, there is virtually no difference between the pay of white and black men. After a similar adjustment, black women actually earn more than white women.

[Source: June O’Neill and David O’Neill, The Declining Importance of Race and Gender in the Labor Market: The Role of Employment Discrimination Policies.]

An important distinction is between individual acts of discrimination and market-wide discrimination. We know there are individual acts of discrimination, because there have been many civil rights lawsuits where compelling evidence has been produced. However, for the market as a whole to discriminate we would need to find cases where Black and white workers are paid different wage rates for identical work. We don’t know of any such cases today.

In a capitalist economy it would be hard for market-wide discrimination to survive. Suppose Black workers were paid less than white workers for the same work. Then an entrepreneur could hire only Black workers, have a cost advantage over his rivals, charge lower prices and capture the market from his rivals.

In South Africa’s Apartheid system and in the U.S. pre-civil-rights South, market-wide discrimination was possible only because it had the backing of the government.

[Source: W. H. Hutt, The Economics of the Colour Bar: A Study of the Economic Origins and Consequences of Racial Segregation in South Africa.]

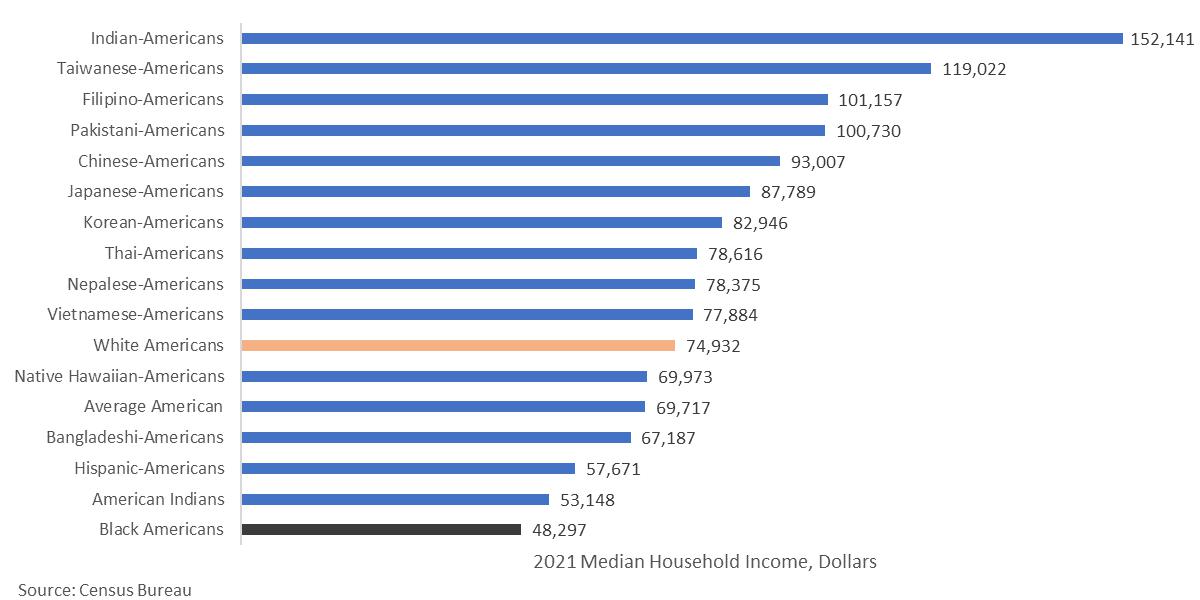

It is sometimes said that white workers are “privileged” or have an advantage in the labor market versus various racial and ethnic groups. But as the chart below shows, white households are very much in the middle of the pack.

Contracting with the private sector is almost always better than government-created jobs.

There are a number of socially desirable goods and services that the private sector doesn’t naturally produce on its own. But as noted, governments around the world are increasingly relying on contracts with private producers rather than government production. The most obvious example in the U.S. at the federal

level is health care. Instead of a government-run system (of the type Sen. Bernie Sanders would prefer),

-

72 percent of enrollees in Medicaid (for the poor) are in private health care plans.

-

More than half of enrollees in Medicare (for the elderly and the disabled) are in private Medicare Advantage plans.

-

Virtually everyone who gets insurance in the Obamacare exchanges (for people who buy their own health insurance) is in a private plan.

We do have some government-run health systems that are holdovers from an earlier era. The Indian Health Service is one. The Veterans Administration is another. Both systems are replete with problems that have persisted for decades. Perhaps for that reason, no one is arguing for expanding these programs to make them available to more people.

To pick one example of the difference between contracting with private suppliers and public production, private Medicare Advantage plans are required to answer a certain type of phone call from enrollees within 8 seconds, and the government uses “secret shoppers” to test the plans’ compliance.

-

In one case, the insurer Elevance (formerly Anthem) answered 23 straight phone calls within 8 seconds, but failed to pick up on the 24th (the company alleges this last call never occurred). Because of that one missed call, the company got a lower quality rating and payments from the government were reduced by $190 million.

-

By contrast, Social Security takes 35 minutes on average before it picks up the phone, and endures no penalty at all.

-

The IRS doesn’t even answer most of its phone calls, picking up the phone only 29 percent of the time.

Even if artificial intelligence is able to perform 30 percent of existing jobs, we do not need to create make-work jobs in order to make everyone better off.

The Luddites were 19th-century English textile workers who opposed the use of certain types of cost-saving machinery, often destroying the machines in clandestine raids. Ever since, the term “Luddite” has been associated with the idea that new inventions and new machinery can substitute for labor and make workers worse off.

Modern economics has a well-established tradition of rejecting the Luddite view, based on a long record in industrial countries of real wage growth even among the least skilled. However, with advances in artificial intelligence, some of our best economists are taking the Luddite view seriously with respect to AI.

As noted, if AI can produce, say, 30 percent of our GDP, that is potentially a good thing. Remember, the robots are not going to eat the food, live in the houses, or drive the cars. Only humans can consume. Also, even if people lose their current jobs, they will almost certainly have opportunities to do other jobs. There will probably never be a time when there is no demand at all for the labor of 30% of our population.

But suppose it did happen. Is the answer to create “make-work” – say, paying people to dig holes and then cover them up? What would that accomplish?

As noted above, the problem AI creates is not a job problem. It is a consumption problem. If AI is doing all the work, we need to make sure everybody shares in the consumption of the goods and services AI produces.

Boston University economist Laurence Kotlikoff and Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs have done some very sophisticated AI modeling and concluded that on some assumptions AI development has the potential to make younger generations worse off. Yet the answer to that development is not to create a lot of make-work jobs. The answer is to redistribute income from those who gain from the transition to those who do not. The authors write:

The Luddites may, therefore, have had a point after all. Advances in machine productivity can indeed commiserate today’s young and future generations. But does this mean that we should smash the machines? Here we can benefit from a bit more insight. Instead of smashing the machines (or more prosaically, preventing their deployment), we can instead use inter-generational tax-and-transfer policy. When the older generation enjoys a windfall from the advance of technology, the government can tax some of

that windfall, and then use the proceeds to improve the wellbeing of today’s youth and of future generations.

With the right choice of tax-and-transfer policies, all generations can benefit from the advance in technology, while under laissez faire, only today’s older generation benefits, and at the expense of all other generations.

[Source: Laurence Kotlikoff and Jeffrey Sachs, Smart Machines and Long-Term Misery, NBER Working Paper 18629, 2013.]

0 Comments