1. Medicare enrollees today receive 3 times as much in benefits as they paid in taxes

The average two-earner family that retired in 2020 will receive $498,000 in inflation-adjusted Medicare benefits over the course of their lives, net of premiums. But they only paid $161,000 into the system in taxes — a ratio of 3.1 to 1. Those retiring in 2030 will receive $645,000 in benefits while paying only $186,000 in taxes — a ratio of 3.5 to 1. With Medicare for All, there is no generation left to shift the burden to. Everyone’s taxes would have to be higher.

https://blog.freopp.org/book-review-modernizing-medicare/?utm_source=substack&utm medium=email

2. Social Security and Medicare are on an impossible spending path.

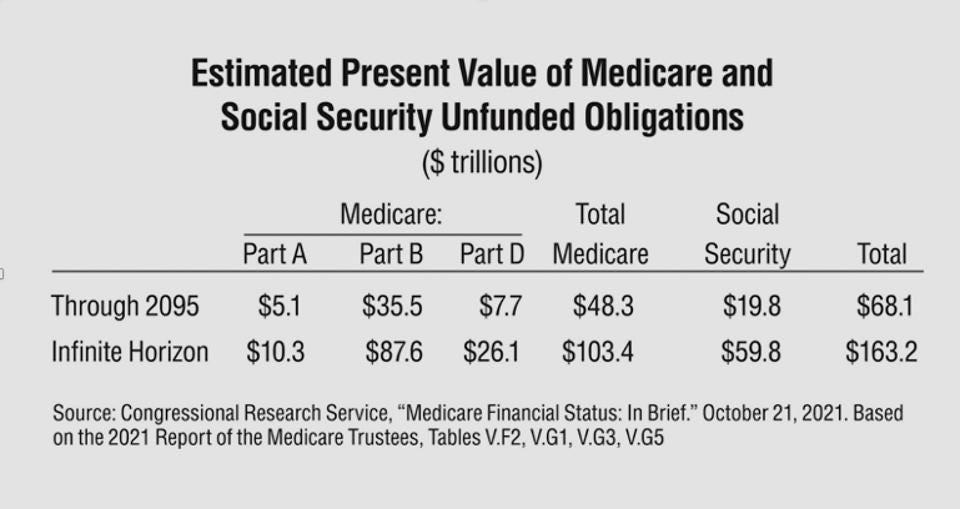

The accompanying table is based on estimates produced by the Social Security and Medicare Trustees. The table shows the value of the unfunded obligations (in current dollars) we have already committed to under current law. Unfunded liabilities are the excess of promises we have made to pay benefits in future years minus the expected tax revenues that are dedicated to pay those benefits.

The first row shows that the discounted value of unfunded promises between now and 2095 is almost three times our national income of $23.4 trillion in 2021. The second row shows that looking indefinitely into the future, there is a $163 trillion unfunded liability that is almost seven times the size of our economy—again in current dollars. In a sound retirement system, we would have $163 trillion in the bank earning interest—so that the funds would be there to pay the bills as they arise. In fact, no money has been saved or invested for future expenses.

3. Medicare and Social Security will not last much longer without reform

In just 9 years (2033), the Social Security Trust Fund will be exhausted and benefits checks will have to be cut by 23 percent. In just four years (2031), the Medicare Part A trust fund will be exhausted and hospital payments will have to be cut by 11 percent.

Bottom line: These two programs have already overpromised and society has not found any politically acceptable way to pay for their current unfunded obligations, let alone find a way to take on new obligations.

https://www.ssa.gov/oact/trsum/

4. Medicare for all would actually increase inequality

Virtually everyone at the bottom on the income ladder who is a U.S. citizen qualifies for Medicaid – health insurance with no premiums and almost no out-of-pocket payment. Everyone else currently has substantial out-of-pocket costs. The bottom fifth of the income spectrum already has the kind of insurance proposed by Sen. Sanders. They either have it or are eligible to enroll. However, people with employer-provided insurance experience salary reductions (for their share of the premium) and lower wages (for the employer’s share). They also face high deductibles, and coinsurance fees. The typical government subsidy is less than half the cost. Most of the people who buy their own insurances pay very low premiums (because of government subsidies), but they face high deductibles and high coinsurance rates. The out-of-pocket exposure for a family of four with Obamacare insurance can be as high as $18,900. While doing almost nothing for those on the bottom rung of the income ladder, Medicare For All would be a substantial boost in economic wellbeing for people on all the higher rungs – if the insurances were provided for free. This would make economic outcomes substantially more unequal than they are today.

https://www.hhs.gov/answers/medicare-and-medicaid/what-is-the-difference-between-m dicare-medicaid/index.html

5. Medicare is Inferior to private health insurance in meeting patient needs

In head-to-head competition between traditional Medicare and private insurance, Medicare has been losing out. Beginning in 2003, beneficiaries have been allowed to enroll in plans offered by Humana, Cigna, UnitedHealth care and other private insurers under the Medicare Advantage program. These private plans are virtually indistinguishable from the private insurance non-seniors have. The private plans are required to provide the same benefits Medicare provides and the government pays a risk-adjusted premium equal to what the government would have spent on the enrollee in traditional Medicare.

https://www.ahip.org/resources/medicare-advantage-demographics

6. Medicare is inferior to private insurance in lowering costs and increasing the quality of care.

Health care spending is 25 percent lower for MA enrollees than for enrollees in traditional Medicare in the same county with the same risk score. After controlling for health status, demographics, and geography, Medicare Advantage enrollees experienced 20-25 percent fewer hospitalizations and made 25-35 percent fewer emergency room visits. They experience lower rates of expensive and ineffective medical procedures in the last few months of life. They produce better outcomes for such conditions as knee and hip replacements, strokes, and heart failure.

https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0179?ref=blog.freopp.org&journalCode=hlthaff

7. Medicare is often the last insurer to adopt innovations that work.

In 2003, the benefit structure of Medicare looked pretty much the same as it did 40 years earlier. But in 1965, drugs were relatively inexpensive and their impact on care relatively modest. Through time, they became more expensive. They also became the most cost-effective medical therapy. When Medicare began covering drugs (through Part D) in 2004 it started providing coverage that virtually all private insurers and all employers had already offered years earlier. Medicare has also been slow to adopt technologies that are becoming more common in the private sector. It took an act of Congress and the Covid pandemic to get Medicare to pay for doctor consultations by phone, email or Skype. It won’t pay for Uber-type house calls at nights and on weekends, although the cost and the wait times are far below those of emergency room visits. Nor will it pay for 24/7 concierge doctor services (usually called direct primary care), now available to seniors for as little as $100 a month – despite the potential to improve access and reduce costs.

https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/BA-128-Goodman-Medi care-for-All.pdf

8. There is nothing Medicare does that employers and private insurers cannot also do.

For many years the Physicians for a National Health Program argued that a single payer health insurer would be a monopsonist (a single buyer) in the market for physicians’ services. It could therefore use this power to bargain down the fees it pays to physicians. However, Medicare doesn’t bargain with anyone. It simply puts out a price and doctors can take it or leave it. Private insurers can do that too. In fact, they can put out a take-it-or-leave-it price lower than what Medicare pays. That’s what has been happening in the (Obamacare) health insurance exchanges, where the most profitable insurers are Medicaid contractors who pay Medicaid rates to providers. Unfortunately, that means that enrollees are often denied access to the best doctors and the best facilities. Obamacare insurance, for example, excludes MD Anderson Center in Houston (cited by US News as the best cancer care facility in the country), Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas (rated as the top medical research center in the world by the British journal Nature) and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Employers and private insurers could be far more aggressive in keeping prices down than they are today and far more aggressive than Medicare is. Canadians who come to the United States for knee and hip replacements (because they get tired of waiting in Canada) pay roughly the same as what Medicare pays. Employers and private insurers could offer the same service to their enrollees. MediBid is a service that offers patients a national exchange where providers submit competitive bids that are routinely less than what Medicare pays.

https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/BA-128-Goodman-Med care-for-All.pdf

9. Medicare for all would be costly

A study by Charles Blahous at the Mercatus Center estimates that Medicare for all would cost $32.6 trillion over the next ten years. Other studies have been in the same ballpark and they imply that we would need a 25% payroll tax. And that assumes that doctors and hospitals provide the same amount of care they provide today, even though they would be paid Medicare rates, which are far below what private insurance has been paying. Without those cuts in provider payments, the needed payroll tax would be closer to 30% and maybe more. Of course, there would be savings on the other side of the ledger. People would no longer have to pay private insurance premiums and out-of-pocket fees. In fact, for the country as a whole this would largely be a financial wash – a huge substitution of public payment for private payment. But remember, in today’s world how much employees and their employers spend on health care is largely a matter of choice. If the cost is too high, they can choose to jettison benefits of marginal value and be more choosy about the doctors and hospitals in their plan’s network. They can also take advantage of medical tourism (traveling to other cities where the costs are lower and the quality is higher) and phone, email and other telemedical innovations described above. The premiums we pay today are voluntary and (absent Obamacare mandates) what people buy with those premiums is a choice individuals and their employers are free to make. With Medicare for all, the patient would have virtually no say in how costs are controlled other than being one of several hundred million potential voters.

https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/BA-128-Goodman-Med care-for-All.pdf

10. The real cost of Medicare includes hidden costs imposed on doctors and taxpayers.

Blahous estimates that the administrative cost of private insurance is 13%, more than twice the 6% it costs to administer Medicare. Single-payer advocates often use this type of comparison to argue that universal Medicare would reduce health care costs. But this estimate ignores the hidden costs Medicare shifts to the providers of care, including the enormous amount of paperwork that is required in order to get paid.

Medicare is the vehicle by which the federal government has been trying to force the entire health care system to adopt electronic medical records – a costly change that appears to have done nothing to increase quality or reduce costs, while making it easier for doctors to “up code” and bill the government for more money.

There are also the social costs of collecting taxes to fund Medicare, including the costs of preparation and filing and the costs of avoiding and evading taxation. By some estimates, the social cost of collecting a dollar of taxes is estimated to be between 25 cents and 44 cents.

Example: To put that in perspective, if the entire $4.5 trillion health care system were paid for by taxes, the social cost of doing that would be as high as $2 trillion. The tax burden itself would be $13,493 per person and the social cost of collecting that amount would be an additional $6,072.

A Milliman & Robertson study estimates that when all costs are included, Medicare and Medicaid spend two-thirds more on administration than private insurance spends.

Single payer advocates are also fond of comparing the administrative costs of healthcare in the United States and Canada – again claiming there is a potential for large savings. But these comparisons invariably include the cost of private insurance premium collection (advertising, agents’ fees, etc.), while ignoring the cost of tax collection to pay for public insurance. Using the most conservative estimate of the social cost of collecting taxes, economist Benjamin Zycher calculates that the excess burden of a universal Medicare program would be twice as high as the administrative costs of universal private coverage. Health economist Chris Conover has more recently estimated the hidden costs of Bernie Sander’s plan for Medicare For All as follows: The deadweight losses generated by collecting the income taxes needed to pay for the plan are between $625 billion to $1.1 trillion per year. (This is the economic cost of tax collection described above.) The excess waste resulting from spending on services that are worth less to the patient than their actual costs — produced by first-dollar coverage — is between $453 to $626 billion per year. The estimated burden for patients due to rationing by waiting would result in at least $152 to $914 billion in annual costs. There would be from $23 to $152 billion in annual social losses stemming from reduced innovation.

All told, the hidden burden of the Sanders plan is between $1.25 and $2.8 trillion. That implies that for every dollar we would be spending on health care, the nation would be burdened by 34 cents to 77 cents in hidden costs. In terms of family budgets, these hidden costs would be about $12,500 to $28,000 per household per year. Conover also estimates that the plan would add $61 trillion to the nation’s unfunded liabilities.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2017/09/28/the-1-reason-bernie-sanders-med icare-for-all-single-payer-plan-is-a-singularly-bad-idea/?sh=6b414c3a5502

https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2017/09/30/the-2-reason-bernie-sanders-med icare-for-all-single-payer-plan-is-a-singularly-bad-idea/?sh=2b017c1c29bb

https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/BA-128-Goodman-Medi care-for-All.pdf

11. Medicare lacks integrated, coordinated care

The typical enrollee in Medicare is paying three premiums to three plans. He qualifies for Medicare Part A (hospital care) on the basis of past payroll taxes. But then he must pay premiums for: Medicare Part B (doctor services), Medicare Part D (drugs), Supplemental (medigap) insurance. The reason for the third plan is to fill all of the holes that are left uncovered in A, B and D. Unfortunately, these plans are run by separate entities who have conflicting economic interests. Consider a diabetic who avoids taking maintenance drugs (the number one cause of complications in chronic illness). This choice is actually good for the drug insurer, who doesn’t have to pay the cost of those drugs. But it is bad for the Part A and B insurer, when the patient shows up at the emergency room and has to be hospitalized. The way to keep A and B costs down is to encourage patients to take their drugs.

So, what’s good for the drug insurer is usually bad for the medical insurer and vice versa.

This problem doesn’t arise in private Medicare Advantage, where enrollees pay one premium to one plan and those plans are generally integrated. Some MA diabetes plans are giving insulin and other maintenance drugs to their enrollees for free. That is because giving away free drugs is cheaper than emergency care and hospital care.

Note: This can’t happen in regular Medicare. “Giving away drugs for free” isn’t included on Medicare’s list of services it pays for.

https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/2022/09/15/medicare-prescription-drugs-a-case-study-in-government-failure/

12. Medicare is a price fixing scheme that is impossible to properly manage

Currently there are more than 1 million practicing doctors in this country and there are 10,000 specific tasks Medicare pays doctors to do. Not every doctor is a candidate to perform every task, but in principle Medicare is setting 10 billion doctor fees, all over the country, every day. How can Medicare make sure the prices are right? It can’t. That would be impossible. What happens when it gets the prices wrong? As any economics book will tell you, wrong prices produce shortages and surpluses. When the price is too high, we get too many doctors offering a service – more than medical needs require. When the price is too low, there will be too few doctors, and we will experience rationing by waiting. Importantly, no one on either side of the market can change a Medicare fee. That can only happen in Washington DC. Private Medicare Advantage plans can pay Medicare fees. But they don’t have to. If there is a shortage of doctors in a particular city, MA plans can pay more in order to attract the services they need. If a hospital has empty beds and looks to fill them, MA plans can negotiate lower fees for its members.

https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/better-way-approach-medicare-s-impossib le-task

13. Medicare’s Fee-for-service care is the opposite of coordinated, integrated care

For doctors who treat Medicare patients, there is a simple rule. If a task is on the list of 10,000, the doctor gets paid. If it is not on the list, they don’t get paid. And that fact has a huge impact on medical practice. As noted, until very recently, the phone was not on the list. Nor was mail, or Zoom. So those types of interactions rarely occurred.

Also, not on the list is helping a patient find a lower-cost way to buy drugs or locating a lower-cost MRI scan. Most important of all, Medicare’s list of 10,000 does not give doctors any reward for keeping patients healthy. The reward for keeping a diabetic out of the emergency room? Zero. How about keeping a patient out of the hospital? Zilch. What about avoiding an amputation? Nada. By contrast, the Medicare Advantage program is the only place in our health care system where a doctor who discovers a change in a patient’s health status can send that information to an insurer (in this case Medicare) and receive a higher premium for the health plan – reflecting the new expected costs of care. In this way, MA plans have financial incentives doctors in traditional Medicare do not have. They have an incentive to discover patient problems early and solve them. And since the MA premiums are fixed, the plan makes money by catching problems early and keeping patients away from the emergency room and out of the hospital. MA doctors are incentivized to keep patients healthy and they have no reason to care whether the way they accomplish that goal involves tasks that are, or are not, on the list of 10,000.

https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/2023/12/17/obamacare-still-desperately-needs-fixing/

0 Comments