By John C. Goodman

Originally posted at Forbes, January 2016

There are vast differences in the health of population groups in the United States. For example at the county level life expectancy for men ranges from a low of 65.9 years in Holmes County, Mississippi to a high of 81.1 years in Fairfax County, Virginia (a wealthy suburb of Washington, DC)—a difference of more than 15 years. Life expectancy for women ranges from 73.5 years Holmes County to 86 years in Collier County, Florida (which includes Naples), a difference of 12 and a half years.

There are also vast differences in behavior which is thought to affect health. At the county level, differences in smoking and excessive drinking vary by a factor of more than two to one. Adult obesity, physical inactivity and lack of access to healthy foods are 50 percent higher in some counties than in others.

Why is that?

Much of the research on inequality of health status has been funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and a summary article in Health Affairs attempted to report on what is known about the “The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health.” From an economist’s perspective, this article is disappointing for three reasons:

- Nowhere does it mention that differences in individual preferences may be responsible for differences in health outcomes.

- Nowhere is there any attempt to gauge the tradeoffs in terms of time and money that different people in different places face in choosing between health and non-health goods and services.

- It implicitly assumes that inequality of health outcomes are bad and that eliminating them should be a public policy priority – regardless of individual preferences and regardless of personal tradeoffs – without ever once justifying those assumptions.

Health researchers all too often tend to completely ignore the economic way of thinking. As a result, they often do not even ask the kinds of questions that in economics would be routine.

What would an economic approach to the inequality of health outcomes look like?

First, it would recognize that good health is only one of many things we value. People have preferences for health versus non-health goods and services and those preferences may differ from person to person.

Second, people face different personal tradeoffs. The acquisition of health requires time, money and other resources. More good health usually means less of something else that people desire.

Third (and this is a value judgement), economists tend to measure wellbeing by how closely people get to whatever it is they want. Moreover (and this is not a value judgement) people’s pursuit of their own wellbeing explains what it is that they do.

At the individual level, there is a demand for health. That demand is influenced by income, wealth, the number of hours in the day, the money and time it takes to achieve an improvement in health and the money price and the time price of other goods and services.

If economists were studying the market for cherry pie and they discovered that the consumption varied a lot across US counties, they would not immediately conclude that this is a “problem” in need of a “solution.” Instead they would probably conclude that consumption differences reflect differences in preferences and maybe also differences in incomes and relative prices.

Now, don’t tell me health care is not like cherry pie. That is an abstract argument of no particular utility.

The real issue is: do people act as though health care is like cherry pie? That is, do people act as though health care is just one of many things they value – all of which trade against each other in competition for our time and money?

There is abundant evidence that that is exactly what they do.

For example, to get people to perform riskier jobs, employers have to pay a wage premium. In these cases, people accept a small decrease in life expectancy in return for what often is a significant increase in income — which means a significant increase in other goods and services they are able to consume. Economists have studied these tradeoffs and determined that the implicit “value of a statistical life year,” to use a term of art, ranges from $50,000 to $150,000. (See this Health Affairs study.)

From an economic point of view, there is no obvious difference between lowering one’s life expectancy by choosing to be a police officer or a fire fighter and lowering one’s life expectancy by smoking, excessive drinking, eating a diet filled with cheese burgers and jelly donuts or choosing a couch potato life style over regular exercise. There are also more exotic ways to lower your life expectancy, usually just for the fun of it: extreme snow skiing, scuba diving in caves, sky diving, hang gliding, spelunking and mountain climbing – to name a few.

Much more needs to be learned about the tradeoffs people face and the choices they make in the light of those tradeoffs. Assuming that life expectancy is superior to all other goals in life is not science, it is opinion – and a very narrow opinion at that.

Let’s leave health care for a moment to consider an issue with a lot of similarities to this discussion. In his new book, Live Free and Prosper, Thomas Saving argues that there is a “demand for income.” In the short run, that demand is constrained by the skills people have to offer to the labor market and the price the market is willing to pay for those skills. However, even in the short run, people can often decide how many hours to work and whether to have more than one job. In the longer run, people can invest in improving the skills they have in order to increase their incomes.

Most discussions of income inequality implicitly assume that individual preferences have virtually no effect on the outcome. In fact, differences in preferences may be the most important determinant of the distribution of income.

Saving cites an experiment with mental patients in a New York hospital who were given tokens for performing such simple tasks as sweeping and mopping floors, sorting laundry, washing dishes, etc. The tokens could then be used to purchase items at an in-hospital store or to buy time on the hospital grounds.

There was no real difference in the ability of the patients to perform these tasks. But there was a significant difference in their desire to earn token income. In fact the distribution of token income among the patients looked very much like the distribution of money income in the United States as a whole.

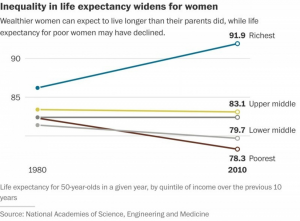

Researchers have long known that there is a relationship between income and health. But it has never been entirely clear why. Take a look at the graph below. It shows that the gains in life expectancy among women in the past 30 years have been concentrated in the top 20 percent of the income distribution. The bottom 40 percent of the population has actually seen a decline in life expectancy. A similar life expectancy gap exists for men.

For people on the political left, this could be taken as evidence that only the rich can afford good medical care. However, a life expectancy gap is occurring worldwide. It even is occurring in Britain, where everyone is supposedly entitled to free health care from the National Health Service.

It may well be that there is an important connection between the demand for health and the demand for income. Exploring that connection means confronting some unresolved issues in the economics of human capital (see Grossman and Gardner) and the economics of time (see Goodman). To the best of my knowledge, this type of serious research is not now being done.

I’ll conclude this essay on a personal note.

I live in a high rise condominium in which there are many homeowners in their 60s and 70s. This is a time of life when physical exercise has significant effects on the health and fitness of people as they age. A few people in my building climb the stairs (all 21 flights) — sometimes two or three times every outing. Others can be seen taking brisk walks out on the streets in the early morning hours. Some use the weights and exercise equipment in the work out room. But most do not exercise at all.

At our annual Christmas party, the physical fitness types tend to avoid the cookies and the cakes, while others – including quite a few overweight folks – dive right in.

I have never regarded this diversity of behavior as a social problem. It has never occurred to me to lecture my neighbors about their behavior or try to get them to change their habits. Why should I? They are all well-educated, have above average incomes and are basically in the same socioeconomic class.

Going forward, differences in health will reflect the different preferences of the different people I live around. And that may not be a bad thing.

This article was originally posted at Forbes on January 20, 2016.

0 Comments