By John C. Goodman

Originally posted at Forbes, June 2016

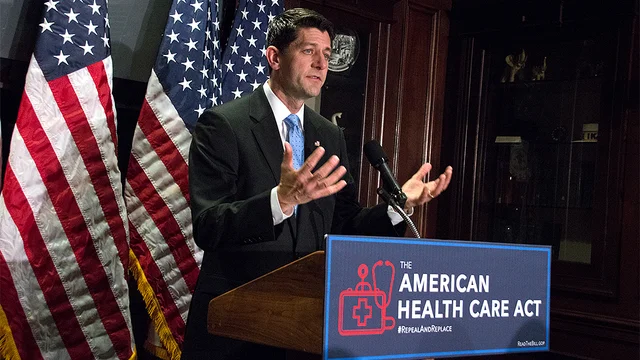

For well over a decade, House Speaker Paul Ryan has been a steadfast supporter of replacing current tax and spending subsidies for health care and health insurance with a universal tax credit. Readers may be surprised to learn that within the health policy community this idea is not regarded as right wing.

Health economists across the ideological spectrum tend to view the current system of subsidies as arbitrary, regressive, inefficient and unfair. Almost everybody knowledgeable about health economics prefers the tax credit approach, including people in the White House (e.g., Jason Furman) and people who helped give us Obamacare (e.g., Zeke Emanuel).

There may be differences over whether the credit should vary by income, age, geography and other factors. There may be differences over the appropriate size of the credit. But the idea of a health tax credit is not even particularly controversial in the health policy community.

For his part, in 2009 Paul Ryan cosponsored the Patients Choice Act, featuring a health tax credit, along with David Nunes (R– CA) in the House and Tom Coburn (R–OK) and Richard Burr (R–NC) in the Senate. Tax credits were also a prominent feature of the original Ryan “Roadmap.” They were central to the agreement he made with Sen. Marco Rubio to draft an alternative to Obamacare before Rubio entered the presidential race. And, of course, the Ryan approach to health reform was also John McCain’s approach – a far more “progressive” reform than the one endorsed by Barack Obama in the 2008 election.

The obvious questions are: Why aren’t more Republican’s supporting the idea. Why aren’t more Democrats? Why isn’t it law?

Three sets of concerns have dampened enthusiasm for the tax credit approach: political concerns, insurance economics concerns and humanitarian concerns. Further, while Ryan has been distracted by many other responsibilities he has gotten very little support from his colleagues or from the think tank community in fleshing out the proposal.

Until now. Over the past year and a half, Rep. Pete Sessions (R-TX), Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and I have been doing the heavy lifting. We now believe we have a version of the Ryan approach which answers all legitimate concerns and does so in a way that should command wide bi-partisan support. In working through all of this we found it necessary to come up with 6 new ideas (out of 12 essential elements) that have not been in any previous proposal.

Let’s take a closer look.

Political Concerns. In the 2008 election, John McCain proposed to tax employer-provided health insurance benefits just like ordinary wages and then give people a fixed sum tax credit in return. This was to be a revenue-neutral switch. Since just about everyone earning less than $100,000 would have come out ahead, the idea should have been immensely popular. However, the vast majority of voters don’t understand how their health insurance is subsidized. Most do not think their health benefits are subsidized at all.

This gave the Obama campaign an ideal opportunity to demagogue the idea. “McCain wants to tax your health insurance,” Barack Obama claimed – implying that everyone would be worse off. The Obama campaign spent an estimated $100 million on TV commercials making that claim, including this one — the most down loaded political commercial in the history of modern politics.

McCain could have responded forcefully. In defending the current employer system, Obama favored allowing the richest, most highly paid people in the business world an opportunity to get unlimited tax subsidies for lavish health care plans, while doing little or nothing for much of the rank and file. But he didn’t. Instead McCain ran away from his plan. As a result, many Republicans became convinced that rational health reform was a losing issue for them.

It took Sen. Cassidy to see a way out of all this. Under the Sessions/Cassidy reform, employer-provided health insurance is not taxed. But employees are not allowed to double dip. If their employer buys insurance for them with pre-tax dollars and the implicit subsidy is less than the tax credit amount, they will be topped up by means of a tax refund. If their implicit subsidy is more, they will be clawed back.

Another political problem is industry and labor opposition. Some time back I spent an entire day at the AFL-CIO building, going over the tax credit approach with labor leaders connected to multi-employer health plans (carpenters, brick layers, truck drivers, etc.). But I don’t have the time to do that with every labor leader or with every CEO of every company. And like the ordinary voter, these folks tend to not understand the current system or the reform we are proposing until they spend time with it.

Our solution: give the employer or the union a choice. They can be grandfathered in the current system or they can choose the tax credit system. Eventually, they will all come around to the tax credit. Until then, there is no reason they should oppose the reform.

Insurance Economics Concerns. The problem of pre-existing conditions is a problem largely created by federal policy. In the past, the tax law encouraged everyone to get group insurance from an employer. But group insurance isn’t portable. When people leave an employer and enter the individual market, they potentially face high premiums if they have an expensive health condition. Any health reform must deal with this problem.

In past proposals, including McCain’s, Republicans have been unclear about what they intended to do. (See this criticism here.) Democrats were equally unclear. But they didn’t sound unclear. Premiums should not vary based on health conditions they said –over and over, leading up to the passage of Obamacare. But they left the insurers free to discriminate against the chronically ill with narrow networks and high deductibles for “specialty drugs.”

Right now the Democrats are vulnerable on this issue – their promises turned out to be bait and switch. But I don’t see any Republican candidates taking advantage of it. And I don’t see conservative think tanks taking Obamacare to task on this issue the way liberal think tanks assailed Ryan and McCain.

Fortunately, the Sessions/Cassidy reform has an answer. It is a form of “free market risk adjustment.” As in the Medicare Advantage program, a health plan would always get an actuarially fair premium when it receives a high cost enrollee from some other plan. That makes the sick just as valuable as the healthy for competitors in the individual marketplace.

One other adjustment needs to be made. Most Republican plans combine a Health Savings Account with tax credits. The former allows deposits with pre-tax income while the latter requires additional premiums to be paid with after-tax dollars. If we want individual self-insurance to be on a level playing field with third party insurance, the savings account must be a Roth account.

Humanitarian Concerns. A constant concern expressed by Democratic critics of Republican health plans can be worded like this: What is the worst thing that can happen to the poorest and most vulnerable patients? How do we know they will be taken care of? Of course, Democrats rarely ask these questions about their own reforms.

Ryan has been vulnerable to criticism for two reasons: (1) he has not explained how he chose the amount of the tax credit he has endorsed or said what he expects the credit would be able to buy; and (2) he has proposed replacing Medicaid with vouchers for private insurance (as did Democratic Sen. Bill Bradley, by the way), but he has not said a great deal about how that would work.

The Sessions/Cassidy approach does six important things:

First, it puts a very clear floor underneath the health care system by anchoring the federal tax credit to the federal government’s contribution to a well-managed, privately administered Medicaid plan. Going forward, the federal tax credit is tied to the cost of Medicaid. So almost everyone should have access to something that looks like Medicaid – at a minimum.

Second, it takes a defined contribution approach – leaving insurers free to compete to see how much they can provide for the credit amount. Unlike Obamacare, benefit packages are allowed to adjust to meet the credit. So there is no reason for anyone to be uninsured because they can’t afford the premium.

Third, it gives everyone who is in it the opportunity to escape Medicaid, claim the tax credit and obtain private insurance instead.

Fourth, at the state’s discretion it allows Medicaid to compete with private insurance – something that should improve the performance of Medicaid for those who choose to rely on it.

Fifth, low-income, mainly healthy families who want more choices than a Medicaid-like plan offers would have the opportunity to claim a partial credit and buy “limited benefit insurance.” These plans would cover, say, 95 percent of all expected medical needs and give families complete protection for their income and assets up to the limits of the policy.

Finally, for every dollar of tax credit that goes unclaimed (because people are uninsured for all or part of a year) a portion of that dollar will be sent to local safety net institutions in the communities where the uninsured live. If people choose to be uninsured and if they cannot pay their medical bills, they will not be denied care. The safety net will always be adequately funded, regardless of how many people are uninsured.

The Sessions/Cassidy reform makes good on Obamacare’s most notable broken promises: universal coverage, cost control and protection for those with pre-existing conditions. It does so with no new taxes, no new spending and massive deregulation.

This article was originally posted at Forbes on June 21, 2016.

0 Comments