This article was originally posted at Forbes.com on May 22, 2018.

For as long as I have been in the field, health economics has been dominated by the idea that the free market can’t work in health care.

Being a contrarian, I’m prepared to ask: What if the free market could work? What would it look like?

Say you need a knee replacement. You would upload your x-rays and other medical information to a secure site. Then, doctors (who have already been screened for trustworthiness, quality, and reliability) would have access to your records and they could submit bids on your care.

As with the sale of other services, three things matter in health care: price, quality and amenities. Price is probably the easiest of the three. In our imaginary free market, if a surgeon can’t tell you what it’s going to cost, there will be no deal from the get-go.

What about quality? There would be a way for you to check on the credentials of your prospective surgeons. Where were they trained? How many years have they been in practice? Any malpractice suits? Any indicators of patient satisfaction or dissatisfaction? Also, you would be able to form a personal relationship with your physician – by phone, by email and by Skype – before consummating a transaction.

What about amenities? You are probably going to spend a day or two recovering in a hospital. What do the rooms look like? How about the food? What facilities exist to accommodate a spouse or caregiver?

In my imaginary world, I envision an online marketplace for knee and hip replacements, diagnostic tests, other common surgical procedures … but wait.

Turns out there is no need to strain my imagination. Each year more than 63,000 Canadians go outside their country for medical care – mainly coming to the United States — because they tire of waiting for free care back home. Many of them are already experiencing what I was only imagining.

Previously, I wrote about Health City Cayman Islands. The facility attracts patients from all over the Caribbean, from Central and South America and from the United States. The cost is about one-third less than what your employer or insurer would pay in the U.S. The quality appears to be better. The amenities, while not four-star, are definitely acceptable.

But do you really have to be a Canadian or fly to the Caribbean to find a real market for medical care? Turns out you don’t.

Welcome to MediBid. I wrote about this company four years ago in Priceless. Since then it has grown from a fledgling enterprise guided by entrepreneur Ralph Weber into a thriving online market for care.

Weber says MediBid got about 3,500 requests last year from patients; and providers made 12,000 bids on those requests. They post all bids made at their Twitter feed, so you can actually see procedure prices streaming. There are more than 1,000 per month.

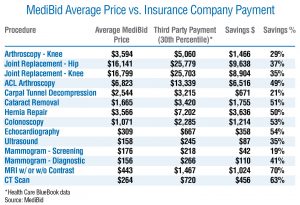

The average knee replacement on MediBid costs around $15,000. The normal charge by U.S. hospitals is around $60,000 and the average insurance payment is about $36,500. A similar range exists for hip replacements, with an average Medibid price of about $19,000.

In Priceless, I wrote that Canadians can come to the U.S. and pay about half as much as we Americans pay. By taking advantage of Medibid, you and I can do the same thing. So can employer health plans.

So which hospitals are giving Canadians and MediBid patients 50% off? It could easily be a hospital right next door to you. Strange as it may seem, hospitals are willing to give traveling patients deals that they won’t give those of us who live nearby.

The reasons? Hospitals believe that if you live in their neighborhood, they’re going to get your business, regardless. Also, after your operation, your insurance company might argue over whether the operation should have been done in the first place. They might argue that there was no pre-authorization. They may argue over price. They may argue over many other things. And when the hospital finally gets its money, it might be a year or two after the fact.

The “medical tourism market,” as it’s sometimes called, has three requirements: (1) you have to be willing to travel and (2) you have to pay up front, and (3) there can be no insurance company interference after the fact.

Take a look at the accompanying table. It compares the average MediBid price with what private insurers are paying at the 30th percentile. That means that 70% of private payments were higher than the number shown. Even at that, MediBid buyers are saving 70% on MRI scans, 63% on CT scans, 53% on colonoscopies and 35% on ultrasounds – just to pick a few examples.

Medibid currently has 265,000 paid subscribers. That is, 265,000 individuals have paid for access to MediBid to shop for medical care, including 83 employer groups. Weber says employers using MediBid generally will save between 40% and 65%. He says they reduced the costs for one employer with 260 people from $2.3 million annually, to only $900,000. Another employer with 285 employees saw a reduction from $2.1 million to $1.1 million.

Here is the final irony. MediBid exists and profits for only one reason: the medical market is currently so imperfect. In the future, as hospitals lose more patients to rivals in other cities, they will likely wise up and begin to compete on price themselves.

When that happens, MediBid may find that its services are no longer needed. So MediBid may be starting something that will eventually put it out of business. But that would be a proper end to a commendable endeavor.

0 Comments