By John C. Goodman

Originally posted at Forbes, March 2016

When people are spending below their deductible they will not spend a dollar unless they expect to get a dollar’s worth of value. But when they are above their deductible they may spend a dollar even though the service is worth far less than what they pay. If they have a 20% coinsurance rate above the deductible, they will tend to spend until health care is worth only 20 cents on the dollar.

As I wrote in a previous post, deductibles and co-insurance payments are very crude devices that give patients very imperfect incentives. A better approach is to allow people to self-insure for whole categories of medical expense, including almost all primary care and most diagnostic tests. Self-insurance is also a promising way to fund much of chronic care.

An ideal way for patients to self-insure is with a Health Savings Account or HSA. A properly designed HSA, combined with third party insurance, can give people the ability to purchase the health care they need, while allowing them to make marginal decisions between health services and others uses of money – undistorted by taxes, third-party reimbursement or any other artificial intrusion. There is no need for deductibles or co-insurance in an ideally designed heath plan.

But wait a minute. Aren’t HSAs associated with inflexible, across-the-board deductibles? They are indeed. In fact high deductibles are required by law. Why is that? Mainly because of an accident of history.

More than 20 years ago, Gerald Musgrave and I did a study of health insurance premiums and we found something very odd. We found that instead of buying a policy with a $100 deductible a person could instead buy a policy with a $1,000 deductible for an annual premium that was $1,000 smaller.

Think about that. In choosing the higher deductible the buyer takes on an additional $900 of exposure. In return, the premium savings allow him to put an additional $1,000 in his bank account. The choice here should be a no brainer, no matter what your expected medical expenses are. The question we asked was: why does anyone buy the low-deductible policy?

We also developed a method of comparing health plans by calculating the price of a dollar of insurance. Among low-deductible options – deductibles ranging from $100 to $1,000 — we found that the cost of insurance was quite high. In this range, the cost of transferring an additional $1 of exposure to an insurance company was 70 to 90 cents and (as noted) sometimes even more than $1. Among high deductible options however, the cost of insurance was quite low. The cost of lowering the deductible, say, from $10,000 to $5,000 was pennies on the dollar.

So, if the cost of high-deductible insurance is cheap and the cost of low-deductible insurance is very expensive, why was low-deductible insurance so popular?

We decided the answer must be the tax law. At the place of work, every dollar of premium paid by an employer was excluded from the taxable income of the employee. But if the employer put that same dollar in a savings account (from which to pay future medical bills), it was subjected to federal, state and local income taxes and a 15.3% (FICA) payroll tax. In other words the tax law subsidized third-party insurance and penalized individual self-insurance.

At that time, the self-employed got a partial deduction for health insurance premiums. And at various times in our history, ordinary individuals also got tax relief for health insurance premiums. But we had never had a formal tax break for a savings account, from which to pay medical expenses.

All that changed in 1996 when Congress created a Medical Savings Account pilot program and again in 2003, when Congress made Health Savings Accounts available to the entire non-elderly population. For the first time in our history, third-party insurance and individual self-insurance were put on a level playing field under the tax law.

Unfortunately, the only distinction most of us saw among health plans at the time was the size of the deductible. Even HMOs seem to fit into this pattern – they were narrow networks with a zero deductible. We even explained the concept of an HSA by reference to the deductible.

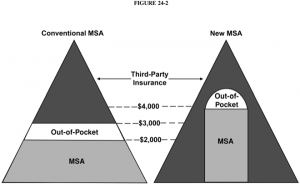

Take a look at the two pyramid diagrams below. In both cases there are many small dollar transactions at the bottom and a few very expensive transactions at the top. We used the diagram on the left to persuade Congress to allow people to raise their deductible and put the premiums savings in a tax free account. Patients would then have economic incentives to be conservative shoppers in the medical marketplace – at least for small dollar items.

We were aided in this effort by Golden Rule Insurance Company executive Pat Rooney, who was selling individual health insurance policies that looked just like the diagram. And we were so successful that Congress essentially codified the diagram. Both in 1996 and in 2003, self-insurance with a tax favored account was made conditional on the stacked pyramid design shown on the left below.

Source: “Designing ideal Health Insurance,” in John C. Goodman, Gerald L. Musgrave and Devon M. Herrick, Lives at Risk: Single-Payer National Health Insurance Around the World.

Here is what we missed. Once you put self-insurance and third party insurance on a level playing field, you open up a whole new world of possibilities. Legislation dictating a deductible limits those possibilities in unfortunate ways.

The proof of this was occurring about the same time in South Africa, where health insurance was almost completely deregulated during the presidency of Nelson Mandela. As a result, South African insurers could introduce any product that was selling in America, in addition to products that we could not have here because of the restrictions in the legislation.

Take drugs for treating chronic illness. Studies show that patient adherence to a drug regime is a major factor in successful treatment. Studies also show that high deductibles discourage compliance. Well before these studies were done, however, South African insurers were guided by common sense: they reduced the deductible to zero for asthma, diabetes and other chronic conditions where zero deductibles were likely to make economic sense. Under US law, by contrast, this is still illegal!

In South Africa today, a typical consumer-directed health plan looks very much like the diagram above on the right. Deductibles are not determined by the expected expense of medical services. They are determined by the desire to allow patients to make their own decisions where personal choice is possible and desirable and to let third-parties pay the bills where the reverse it is true.

This article was originally published at Forbes on March 9, 2016.

0 Comments